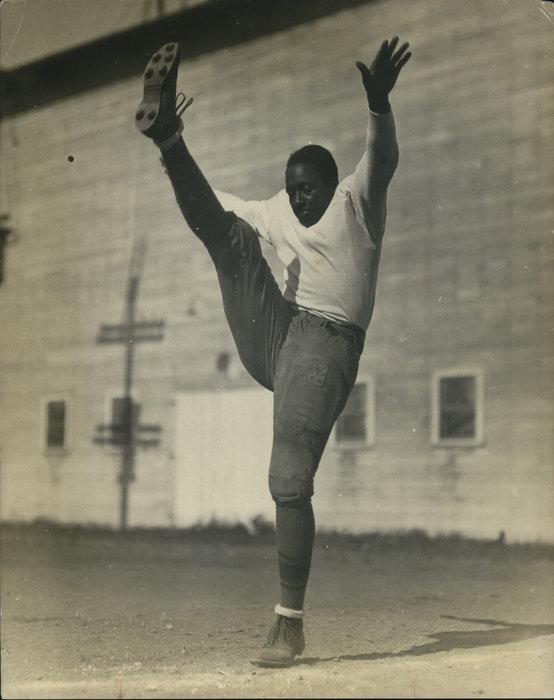

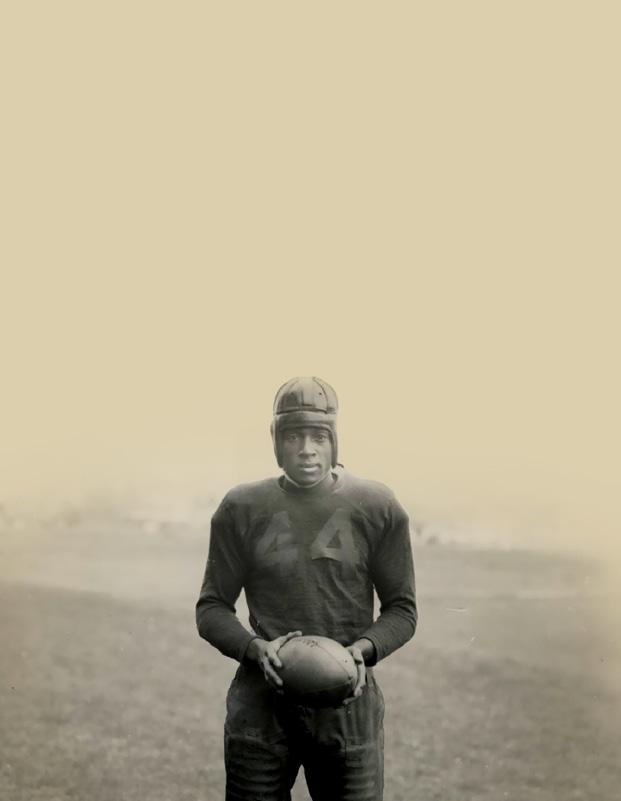

Oregon Black History Spotlight: JOE LILLARD

By Oregon Black Pioneers

Joe Lillard was an early Black athlete at the University of Oregon. He was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1905, but moved with his family soon after to Mason City, Iowa. Joe’s father abandoned the family when Joe was a toddler, and his mother died when he was just 9 years old. Relatives cared for Lillard and his sister for a few years, but by the time Joe was a teenager, the two were living in a boarding school in Eldora, Iowa. Joe was forced to work in the school’s boiler room to pay for their residency.

Joe Lillard was an early Black athlete at the University of Oregon. He was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1905, but moved with his family soon after to Mason City, Iowa. Joe’s father abandoned the family when Joe was a toddler, and his mother died when he was just 9 years old. Relatives cared for Lillard and his sister for a few years, but by the time Joe was a teenager, the two were living in a boarding school in Eldora, Iowa. Joe was forced to work in the school’s boiler room to pay for their residency.

While attending and working at the school, Lillard took an interest in sports. He competed on the school’s baseball, basketball, and track teams, but was especially gifted at football. As a junior, he transferred to Mason City High School, where he made All State honors in basketball and football. In 1927, Joe graduated high school, got married, and started working as a chauffeur. All the while, he still hoped to find opportunities in athletics. He joined a Black barnstorming baseball team and played guard for the Savoy Big Five, the predecessors of the Harlem Globetrotters.

Joe tried to enroll at the University of Minnesota after meeting UM football coach Clarence Spears, but the university would not accept him. In 1930, Spears became the head football coach at University of Oregon. When Joe Lillard applied to UO, he was accepted, and joined the Ducks’ basketball and football teams.

Joe would be the UO football team’s starting quarterback. Oregon had had Black players since 1926, but Lillard’s arrival drew huge excitement. The Eugene Guard even described Lillard as “God’s colored gift to Oregon.” Once the season began, Lillard’s talent was evident. After leading the Ducks to a victory over Oregon State University in his first game, the paper wrote, “The score wasn’t written in digits… rather, in the fleet feet and the white heart of Joe Lillard, who, because he was black, was smothered again and again, jumped on, kneed and knocked out, but who wouldn’t leave the game, even after he was deliberately flattened unconscious from an obvious roughing tactic.”

Lillard helped the Ducks finish with a 7–2 season and was excited for the next year. However, the Pacific Coast Conference had learned of Lillard’s semi-pro baseball career and declared him ineligible for collegiate athletics in 1931. Although the conference had no evidence Lillard was ever paid to play baseball, they ruled that he had played under a false identity, which merited automatic disqualification. It was a technicality that some thought was racially motivated. The Oregon Daily Emerald reported, “The ‘gentleman’s agreement’ is still in effect!”

Lillard’s college football career was over, so he left the school and entered the National Football League, playing halfback for the Chicago Cardinals. He was the team’s leading scorer in his first year, but the next season, 1934, was the beginning of the NFL’s own gentleman’s agreement, prohibiting Black players from the league. Lillard became the last Black player to play in the NFL until 1946.